Excerpted from “Hadzabe: By the Light of a Million Fires” by Daudi Peterson, Richard Baalow and Jon Cox

We are Hadzabe, we are Tanzanians. Our people number about 1000 and we live in the Lake Eyasi Valley and surrounding hills. In our oral history we have always lived here. We have no record of living somewhere else. Our language is not related to any of the different languages of our neighbors who have moved into this area more recently.

This is OUR story as told to us by our fathers and to them by their fathers by the light of a million fires. Watching the sparks fly into the African night, we listen mesmerized and watch as the elders enact our history–the history of humanity–before our very eyes. They hold our wisdom and their stories–our stories–become alive, attaching themselves to our minds so that they will never be forgotten. And, when the time comes, we will pass them on to our own children as the sparks of another fire pierce the night. These stories are an essential part of our early schooling but when dawn breaks, it brings new lessons and the learning process continues as we tag along behind our parents while they hunt and forage.

This is OUR story as told to us by our fathers and to them by their fathers by the light of a million fires. Watching the sparks fly into the African night, we listen mesmerized and watch as the elders enact our history–the history of humanity–before our very eyes. They hold our wisdom and their stories–our stories–become alive, attaching themselves to our minds so that they will never be forgotten. And, when the time comes, we will pass them on to our own children as the sparks of another fire pierce the night. These stories are an essential part of our early schooling but when dawn breaks, it brings new lessons and the learning process continues as we tag along behind our parents while they hunt and forage.

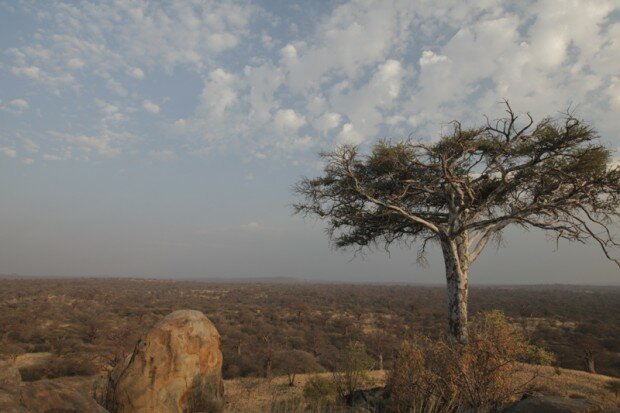

We are hunter-gatherers. We live off the land and have done so successfully for thousands of years even though our homeland in the Lake Eyasi region is harsh and dry. Our neighboring tribes, dependent on water greedy crops such as maize, and on large herds of cattle and goats, often face recurring famine. Severe droughts force them to turn to the government for help and famine relief. We, on the other hand, have no record of severe famine since we rely on many different plants and animals, all of which are adapted to this particular environment.

Unlike many African tribes where the women are subordinate to the men, our women stand proud beside us, certain in the knowledge that their gathering of food alone could sustain us. We the Hadzabe love meat, fat and honey above all else, but these are only supplements to our predominately plant-based diet.

Unlike many African tribes where the women are subordinate to the men, our women stand proud beside us, certain in the knowledge that their gathering of food alone could sustain us. We the Hadzabe love meat, fat and honey above all else, but these are only supplements to our predominately plant-based diet.

Our God, Haine, along with Ishoko the Sun and Seeta the Moon, have provided well for us. Every day we set out with the sun to eat from nature’s table. The men sharpen their arrows, tighten their bowstrings and focus their eyes. Thanks to the skills passed on to us by our fathers, we can hunt successfully enough to thrive one day to the next. Sometimes the honeyguide, an insistent little bird, will distract us with its rattling call and the promise of sweet honey melting in our mouths. Who are we to deny it! We follow it through the bush as it hops from tree to tree leading us towards a beehive.

The women too sharpen their digging sticks and grab their bags at daybreak. They are sure to come back with enough tubers and fruits to feed us all. No matter the time of the year, nor the fickleness of the weather, there is always some bush bearing fruit or some tuber brimming with moisture lurking just beneath the ground, waiting to be harvested. When the abundant fruits from the baobab trees ripen, they provide enough nourishment to keep us all healthy for months to come.

Before the sun reaches its summit, almost everyone will be back at camp with full stomachs and there will be no need to go out again until the sun is low in the sky. For the men, the hottest hours of the day are spent making bows and arrows, or resting, smoking our stone pipes and telling stories. Some days the men brew poison from the sap of the desert rose or grind the other poison we use, to smear on their arrows, replacing those lost during the morning hunt. The women tend to the children, make beaded jewelry, and pound the pulp of the baobab fruits into flour for porridge, while others rest and chatter incessantly in our ancient click language.

If a man has not returned by noon, there is no cause for worry but instead reason for hope. It could be that he has been led far away by a honeyguide or even better, he might be following the spoor of a big animal hit by his poisoned arrow. If the latter is true, there will be enough meat to feast on until our stomachs distend and the last bit of fat and sinew is picked off the bones. Even the bones will be cracked open for the delicious marrow within. Nothing will be wasted and even the hyenas will skulk away, tail between their legs, to whoop their disappointment to the stars.

Because we know for certainty that each day will provide us with food, we don’t need to store food for tomorrow and we share whatever we have today with everyone. But to ensure that we have enough for tomorrow, we live a nomadic life that allows the land to recover in our wake. When we return, we find the land healthy and plentiful once again.

By using no snares or traps and hunting only with our self-made bows and arrows, we have no lasting impact on the wildlife populations. We don’t cut trees to build houses or enclosures for domestic animals and crop storage. Like the rest of the world we depend on trees but we do not destroy them. We drink directly from springs and return for more when we are thirsty. Digging out the springs for crops and livestock lowers the water table, making it impossible for the wild animals to drink. If the wild animals find no water, they will be forced to move on and where would that leave us? Our houses are only temporary shelters built out of dry grass thrown over a frame of intertwined branches, like a bird nest upside down. They melt back into the ground as soon as we move on and we build new ones when we return.

By using no snares or traps and hunting only with our self-made bows and arrows, we have no lasting impact on the wildlife populations. We don’t cut trees to build houses or enclosures for domestic animals and crop storage. Like the rest of the world we depend on trees but we do not destroy them. We drink directly from springs and return for more when we are thirsty. Digging out the springs for crops and livestock lowers the water table, making it impossible for the wild animals to drink. If the wild animals find no water, they will be forced to move on and where would that leave us? Our houses are only temporary shelters built out of dry grass thrown over a frame of intertwined branches, like a bird nest upside down. They melt back into the ground as soon as we move on and we build new ones when we return.

We live in harmony with our environment because we live and depend directly on the land. We look after it and it looks after us. We have lived in the Eyasi region for thousands of years and have left no mark upon the land. This, ironically, seems to be the cause of our present plight. Other tribes, passing through this area must have thought it uninhabited and so settled here. We didn’t have a problem with that initially since our land was plentiful and could sustain us all. But we soon realized the harm caused to the environment by farming, by cutting trees for cattle enclosures and houses, by making charcoal fuel out of trees, by huge herds of cattle overgrazing the land, and by digging waterholes until the water sources retreat deep into the ground.

Finally when we decided to complain and make a stand for our land, our pleas went unheeded.

We are discriminated against because we are hunter-gatherers. People who don’t understand our economy and culture treat us as if we are backward or primitive. Because we have maintained our environment in its natural state, they consider our land empty and unused and our basic rights as Tanzanians are denied.

Over the last few decades we have lost more than three quarters of our land to practices that continue to destroy it. Contrary to popular opinion, we Hadzabe are not opposed to development. We are, however, opposed to the unsustainable use of the land. We believe it is possible to develop while keeping our cultural heritage and putting our profound knowledge of the environment to good and sustainable use. Our first priority, therefore, is to obtain our rights over the land that has supported us for thousands of years and which we have preserved intact for the generations to come.

As we lose our land and the plants and animals we depend on, we lose the only foundation that will enable us to develop alongside our fellow Tanzanians. The continued loss of our natural environment will leave us homeless and its destruction will not benefit our neighbors or our nation of Tanzania, now or into the future. Our fellow citizens will lose a culture rich in knowledge accumulated over millennia–knowledge that complements the lives of both our children and theirs.

As Hadzabe we wish to promote the understanding of our culture and economy–an understanding that will lead to greater respect for our land and our basic human rights. Only a better understanding and respect for who we are will allow us to join the future with dignity as Tanzanians.

“We are Tanzanians, we are Hadzabe.”

“We are Tanzanians, we are Hadzabe.”